For starters, January didn’t exist for the Romans. Here’s how their ancient calendar evolved into our modern system of marking time.

In the early Roman calendar—which was closely tied to the harvest—the winter months went unnamed until the 7th century B.C. It would take several more centuries to establish January 1 as the start of the new year. Early depictions of the month typically featured feasts such as this 13th-century stained glass window at the Cathedral of St. Etienne in Bourges, France.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PHOTOGRAPH VIA BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

In the dark days of winter, a new year begins. But January wasn’t always the start of the new year. At the dawn of modern calendar-keeping, the winter months went unnamed in the calendars that gave rise to today’s most popular system of marking time.

Named after Janus, the god of time, transitions, and beginnings, January was an invention of the ancient Romans. Here’s the story of the month’s wild ride—a tale of astronomical miscalculation, political tweaking, and calendar confusion.

The first Roman calendar

Humans have been marking time on calendars for at least 10,000 years, but the methods they used varied from the start. The Mesolithic people of Britain tracked the phases of the moon. Ancient Egyptians looked to the sun. And the Chinese combined both methods into a lunisolar calendar that’s still used today.

(Why Lunar New Year typically prompts the world’s largest annual migration.)

The modern calendar used in most of the world, though, evolved during the Roman Republic. Though it was attributed to Romulus, the polity’s founder and first king, it’s likely the calendar developed from other dating systems designed by the Babylonians, Etruscans, and ancient Greeks.

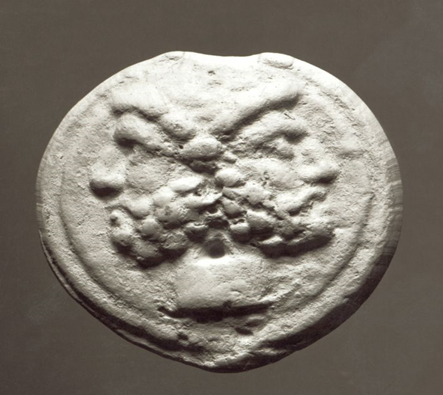

The first month of the new year is named for Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and transitions. Janus is typically depicted as having two faces, such as on this metal Roman coin dating between 753 B.C. and A.D. 476.

PHOTOGRAPH BY PHOTOGRAPH VIA BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

As Romans’ scientific knowledge and social structures changed over time, so did their calendar. The Romans tweaked their official calendar several times from the republic’s founding in 509 B.C. until its dissolution in 27 B.C.

The first iteration was a scant 10 months long and paid homage to what counted in early Roman society: agriculture and religious ritual. The 304-day calendar year began in March (Martius), named after the Roman god Mars. It continued until December, which was harvest time in temperate Rome.

The Romans linked each year to the date of the city’s founding. Thus, the modern year 753 B.C. was considered year one in ancient Rome.

The initial calendar included six 30-day months and four 31-day months. The first four months were named for gods like Juno (June); the last six were consecutively numbered in Latin, giving rise to month names such as September (the seventh month, named after the Latin word for seven, septem). When the harvest ended, so did the calendar; the winter months were simply unnamed.

Rome’s lunar calendar

The 10-month calendar didn’t last long, though. In the seventh century B.C., around the reign of Rome’s second king, Numa Pompilius, the calendar received a lunar makeover. The revision involved adding 50 days and borrowing a day from each of the 10 existing months to create two new, 28-day-long winter months: Ianuarius (honouring the god Janus) and Februarius (honoring Februa, a Roman purification festival).

The new calendar was anything but perfect. Since Romans believed odd numbers were auspicious, they attempted to divide the year into odd-numbered months; the only exception was February, which was at the end of the year and considered unlucky. There was another issue: The calendar relied on the moon, not the sun. Since the moon’s cycle is 29.5 days, the calendar regularly fell out of sync with the seasons it was intended to mark.

In an attempt to clear up the confusion, Romans observed an extra month, called Mercedonius, every two or three years. But it wasn’t applied consistently, and various rulers added to the confusion by renaming months.

“The situation was made worse because the calendar was not a publicly available document,” writes historian Robert A. Hatch. “It was guarded by the priests whose job it was to make it work and determine the dates of religious holidays, festivals, and the days when business could and could not be conducted.”

The birth of the Julian calendar

Finally, in 45 B.C., Julius Caesar demanded a reformed version that became known as the Julian calendar. It was designed by Sosigenes of Alexandria, an astronomer and mathematician who proposed a 365-day calendar with a leap year every four years. Though he had overestimated the length of the year by about 11 minutes, the calendar was now mostly in sync with the sun.

(Leap year saved our societies from chaos—for now, at least.)

Caesar’s new calendar had another innovation: a new year beginning on January 1, the day its consuls—a pair of men who constituted the republic’s executive branch—took office. But though the Julian calendar would stick around for centuries, the date of its new year wasn’t always honoured by its adopters. Instead, Christians celebrated the new year on various feast days.

Aside from a few tweaks by other Roman rulers, the Julian calendar remained largely the same until 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII adjusted the calendar to more accurately reflect the amount of time it takes for the Earth to travel around the sun. The old calendar had been 365.25 days long; the new calendar was 365.2425 days long. The new calendar also shifted the dates, which had drifted by about two weeks, back in sync with seasonal shifts.

Only with Gregory’s 1582 reform did January 1 really stick as the beginning of the new year—for many. Not everyone switched to the new Gregorian calendar, and as a result the Christmas holiday falls in January for members of Eastern Orthodox churches.

(Here’s why the Orthodox church rejected the Gregorian calendar.)

While the modern world mainly syncs to the Gregorian calendar, other calendars have lived on. As a result, different cultures acknowledge different dates as the start of the new year—and have festivals, rituals and holidays, like Nowruz, Rosh Hashanah, and Chinese New Year—to celebrate.

whoah this blog is wonderful i really like reading your articles. Keep up the great paintings! You realize, a lot of people are hunting round for this info, you could help them greatly.

I have read so many posts about the blogger lovers however this post is really a good piece of writing, keep it up